A robust Rhode Island food system would support environmental justice and help mitigate climate change. The current corporate-ruled system is collapsing under the weight of a changing climate, even as the barriers to food equality grow.

By Frank Carini, ecoRINews

PROVIDENCE — Seven weeks before the ceremonial ribbon cutting and months before the premises would be ready to host their businesses, the owners of the new building’s two restaurants whetted their appetite for local food with a visit to 404 Broad St.

Adena “Bean” Marcelino, the owner and operator of Black Beans PVD, and Darell Douglas and Giovanna Rodriguez, the owners of D’s Spot, roamed the construction-equipment lined halls and rooms of Southside Community Land Trust’s (SCLT) soon-to-be headquarters in wonderment. They couldn’t wait to get started in their new digs.

The three food-related businesses, including Luna Walker’s Lu’s Mini Mart, are owned by people of color. Their “Healthy Food Hub” grand opening is expected sometime in September, about a month after the rest of the facility opens. The trio of businesses are partnering closely with SCLT’s vision to expand local residents’ affordable, healthy food options.

Black Beans PVD is a “soul-food-driven, all-from-scratch kitchen” currently operating at 55 Cromwell St. It serves homestyle meals and desserts. D’s Spot in Pawtucket is known for its chicken and waffles, but the plan is to create a menu with a healthier focus when the restaurant moves to Providence. Lu’s Mini Mart, currently operating at 200 Mineral Spring Ave. in Pawtucket, will operate a small grocery with traditional ingredients from Liberia and West Africa. Walker plans to tap into the bounty harvested by Liberian and West African farmers who grow food in SCLT community gardens and farms.

Marcelino, a psychology major who spent 13 years working in the social services sector, is big into food, especially local, affordable, culturally connected cuisine served in smaller, healthier portions. She likes how food connects people from one generation to the next and how it introduces people to different cultures.

The longtime West End resident opened Black Beans PVD in December 2019 as a fine-dining club that quickly transitioned to a grab-and-go model when the pandemic struck.

“Overfeeding people drives up the cost,” said Marcelino, who was born and raised in Providence. “Smaller portions feed people reasonably and healthier. People need access to food that doesn’t jack up your blood pressure.”

She believes people living in poverty should have the same freedom to choose healthy food and be able to dine out on occasion. She creates her menu with low-income families in mind, saying she can feed a family of four for $14.

SCLT, which was long headquartered on Somerset Street in a three-story Victorian, was founded four decades ago by local residents and newly arrived Hmong refugees who reclaimed an abandoned parcel by working together to create the neighborhood’s first community garden. For the past 40 years, the organization has helped people in Greater Providence’s low-income neighborhoods grow and buy sustainably harvested, culturally familiar produce.

The nonprofit’s new 12,000-square-foot building at 404 Broad St. in the city’s upper South Side will feature a farm-to-market processing center and the aforementioned food retail enterprises in more-affordable space. Executive director Margaret DeVos and board president Rochelle Lee led a May 4 tour of the still-in-the-works facility for invited guests, including media and future tenants.

DeVos said the organization’s new headquarters and the additional space will help it further its mission to expand the supply of “locally grown, culturally appealing healthy food to the community.” The organization focuses on the food needs of Providence, Central Falls, and Pawtucket.

She said the Broad Street facility will further SCLT’s mission to address food insecurity, a problem that impacts one in six Rhode Islanders, better support its work to build a more equitable local food system, and help farmers growing local food lower their operation costs.

“We want to create structure so farmers are successful,” DeVos said. “Our network of community gardens used by neighborhood residents are a driver of public health.”

Lee said this network of “just gardens” grow culturally significant foods — Nicaraguan and Cambodian growers are also well represented — and the new facility will “open doors to more plant-based food.”

“We want to elevate BIPOC [Black, Indigenous, and people of color] into leadership roles and educate the greater community about how food helps make you healthier,” said Lee, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology graduate who has been with SCLT since the beginning. “Green food fights obesity and diabetes.”

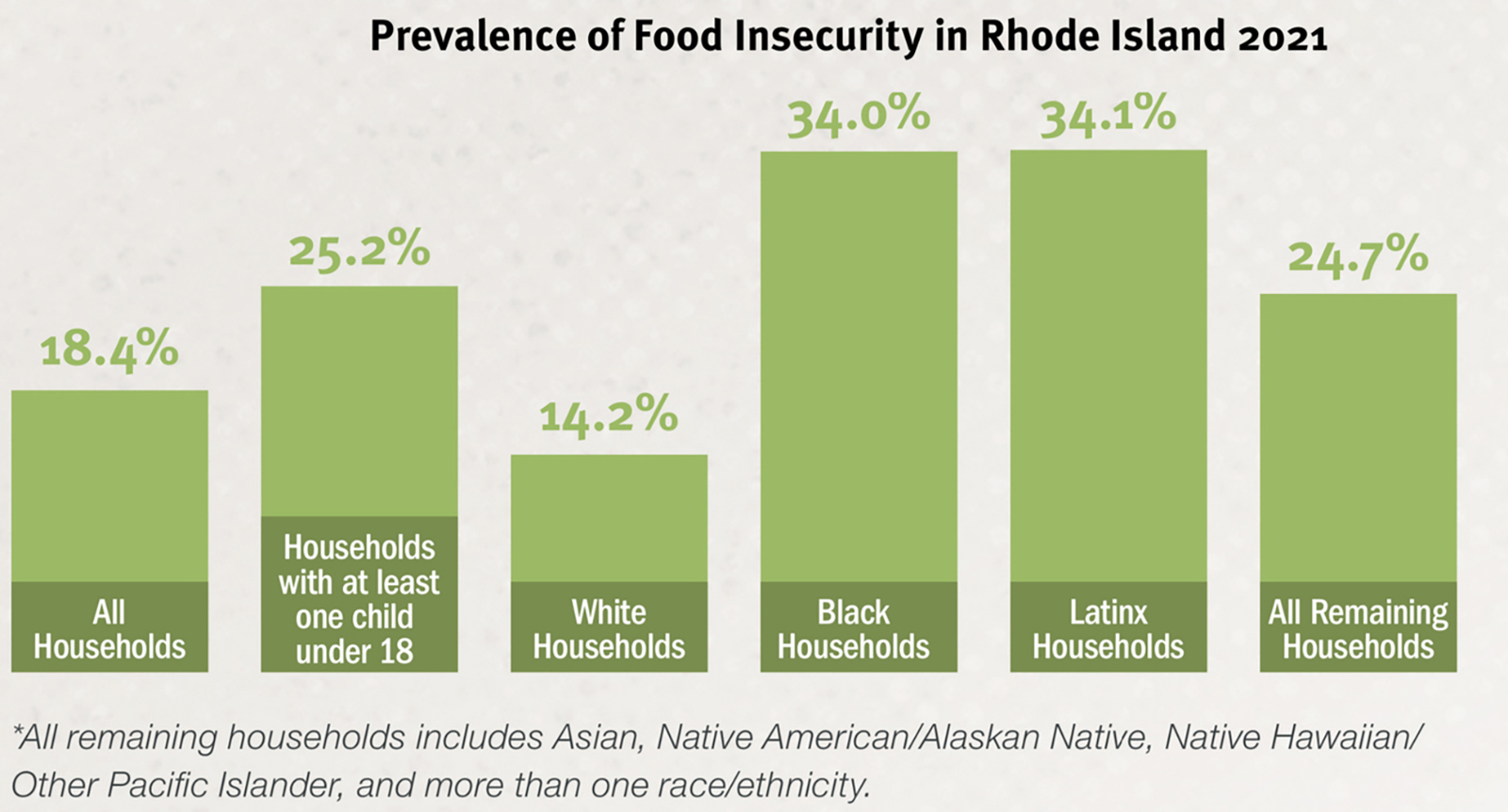

In 2021, among all households in Rhode Island, more than 18% couldn’t meet their basic food needs. The risk of hunger was even higher for families with children. (Rhode Island Community Food Bank)

In 2021, among all households in Rhode Island, more than 18% couldn’t meet their basic food needs. The risk of hunger was even higher for families with children. (Rhode Island Community Food Bank)

Food justice for all

Food justice is about addressing access to healthy and affordable food for low-wealth and marginalized communities. It seeks to ensure the benefits and risks of where, what, and how food is grown, accessed, distributed, and transported are shared equally.

Many neighborhoods in metropolitan areas, including in Rhode Island’s urban core, have little to no access to fresh food or full-service grocery stores — a situation often referred to as living in a “food desert.” Other marginalized communities are surrounded by “food swamps,” areas in which a large amount of processed foods, such as fast food and convenience-store fare, is available with limited healthy options.

“It’s important to develop food systems that support better public health,” said DeVos, who has been SCLT’s executive director for the past decade.

One solution to this environmental justice problem is to encourage the growing of local food. To support such an effort, the availability of land is paramount — a difficult proposition in a state that features some of the highest-priced farmland in the country. (Also, Rhode Island’s transition to suburbanization has cost the state 80% of its farmland since 1945.)

This lack of access to affordable farmland threatens the state’s agricultural sector, according to the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management.

As of 2017, Rhode Island had 1,043 farms and 56,864 acres in agricultural production, according to the most-recent USDA Census of Agriculture. The census is taken once every five years; the next one is scheduled for this year.

Disappearing farmland — an ongoing concern as older farmers age out of the demanding work and sell/lease their property to developers because of a lack of younger interest in the financially challenging occupation — and the high cost of what remains are forcing nonprofits and government agencies to get creative.

The coronavirus pandemic showed how quickly the global food system can be disrupted. For many environmental justice advocates, building a better local food system is vital to feeding the hungry and helping to mitigate the climate crisis.

At an April Advisory Board meeting of the state’s Executive Climate Change Coordinating Council, Rhode Island Food Policy Council network director Nessa Richman joined Julianne Stelmaszyk, director of food strategy for Rhode Island Commerce, to present facts and findings related to the environmental impacts of the state’s food system. Their presentation centered around the state’s Relish Rhody food strategy.

The 40-page strategy, published in 2017, “envisions a sustainable, equitable food system that is uniquely Rhode Island; one that builds on our traditions, strengths, and history while encouraging innovation and supporting the regional goal of 50 percent of the food eaten in New England be produced in the region by 2060.”

The strategy lists recommended near-term actions steps that include: expanding the preservation of active farmland; reducing transportation barriers to food access; reducing the price and increasing access to healthful foods; supporting the development of community gardens; and creating a statewide hunger task force to lead efforts to reduce food insecurity from 12.8% to below 10% by 2020.

In 2021, among all households in Rhode Island, 18.4% couldn’t meet their basic food needs, according to the Rhode Island Community Food Bank. Black and Latino households had the highest percentage of food insecurity at 34%.

From 2017 to 2019, food insecurity in Rhode Island affected 9.1% of households, and in 2020 touched 25.2% — most of which was tied to the explosion of COVID. Last year, to meet the state’s high demand for food assistance, the Community Food Bank distributed a record amount of food (15.1 million pounds) through its statewide network of partner agencies.

SCLT Board President Rochelle Lee speaks at the June 24 ribbon cutting for the organization’s new ‘Healthy Food Hub.’ Executive Director Margaret DeVos is behind her. (Photo credit: Shana Santow)

“We still haven’t done a good job with the narrative, because I think most people think people who are hungry are just poor people, but not really,” SCLT board president Lee said during a Zoom call ecoRI News had with her and DeVos a day before the June 24 ribbon cutting. “They’re kids, they’re students, they’re old people. They live in every neighborhood and community. Somewhere along the line maybe we’ll figure it out … and it won’t be a matter of the have and have-nots.”

DeVos said the emergency food system is vital, but she noted bouncing from one crisis to another in emergency mode doesn’t address the underlying problem.

“People need food; let’s give them healthy food,” she said. “But every single day, every single economic downturn, every single time inflation gets higher, every single time unemployment gets higher we have a run on food banks. We have to be thinking beyond investing in food banks and purchasing emergency food in that moment of crisis.”

The Community Food Bank’s 2021 report found that: critical government programs and benefits are ending, despite the continued hardships faced by low-income Rhode Islanders; and racial and ethnic inequities in food security persist.

Early last year, the Rhode Island Food Policy Council and the Rhode Island Department of Health (DOH) announced a new partnership to coordinate the Rhode Island Hunger Elimination Task Force. In a press release announcing this partnership, Richman is quoted: “We envision a state where all people have access to affordable, fresh, nutritious, and culturally-relevant food.”

Nicole Alexander-Scott, then the DOH director, is also quoted: “Over 25% of households are worried about having adequate food as a result of the pandemic. This represents the highest level of food insecurity recorded in Rhode Island in 20 years. Black and Latinx communities have been hardest hit by the COVID-19 pandemic and also experience higher rates of food insecurity.”

During a June 24 interview with ecoRI News, Richman said food access and security are tied to structural and environmental racism that have created economic disparities. She said healthy food should be seen as a human right and the structural barriers — e.g., lack of public transit; not enough businesses that accept food stamps; lack of services that deliver healthy, local, affordable food to the sick, disabled, and elderly — restricting access torn down.

“Food access problems exist because of structural inequities in our society that lead to unequal outcomes,” she said. “Those are the root causes and there are solutions that address those root causes, and those are mainly the community-based solutions that are being led by the people who are most affected by the inequities.”

Caitlin Mandel, the Food Policy Council’s food access and equity program manager, agreed, saying “access to nutritional food is a right.”

“It’s a health issue, when people don’t have that it affects long-term health outcomes, which affects everybody,” Mandel said.

They both said the infrastructure and people supporting Rhode Island’s local food system — community gardens, farmers, fishermen, small businesses, and nonprofits — require long-term state investment.

The Hunger Elimination Task Force held four meetings last year. Its second meeting of this year was held in early May. The next meeting, also a virtual one, is scheduled for July 26 from 2-3:30 p.m.

SCLT’s Lee called Rhode Island’s collective efforts to address food insecurity and increase access to healthy food “noble,” but noted the corporate-controlled food system isn’t easy to dismantle.

“There’s a lot of institutionalized food that has not contributed toward addressing food insecurity itself or nutritional security either,” she said.

The consumption of healthy, local food, especially in urban areas, leads to better public health. (Photo credit: Joanna Detz/ecoRI News)

The consumption of healthy, local food, especially in urban areas, leads to better public health. (Photo credit: Joanna Detz/ecoRI News)

Nurturing local food

Much of the work required to improve access to local food and feed the food insecure falls to small-scale growers, nonprofits, and volunteers.

Since 1981, SCLT has grown to run a number of programs that feed more than 15,000 people annually. It provides low-cost land leases to 40 farmers who supply fresh fruits and vegetables to farmers markets, food businesses, restaurants, and community-supported agriculture customers. It operates 21 community gardens in Providence, Pawtucket, and Central Falls, and partners with schools and housing and community organizations to manage another 37 gardens. SCLT manages three production farms in Providence and Pawtucket that practice “biointensive, small-scale agricultural production.”

A total of 570 garden plots are in use at SCLT-owned properties, and 85% of SCLT gardeners are living below the poverty line, according to the organization’s most-recent annual report.

Farm Fresh Rhode Island, also based in Providence, in a 60,000-square-foot facility at 10 Sims Ave., operates six seasonal farmers markets and a year-round market primarily in areas with limited access to fresh, local food. The nonprofit has been working to provide better access to local food since 2004.

Hope & Main, at 691 Main St. in Warren, is a culinary incubator that helps community food entrepreneurs jump-start their business to create a “more just, sustainable and resilient local food economy.” Since 2014, the nonprofit has helped launch 300 small businesses.

Eating with the Ecosystem and the Commercial Fisheries Center of Rhode Island have been working to bring under-appreciated species abundant in local waters, such as scup, to low-wealth families and food pantries in the Ocean State.

The consumption of healthy, local food, especially in urban areas, leads to better human health and helps mitigate the climate crisis, according to local food advocates. They note that such efforts improve human and environmental well-being, empower communities, and build resilient neighborhoods. The greening of the environment created by the growing of local food also reduces the heat-island effect, filters polluted air, and helps reduce flooding.

But Americans get more than 50% of their daily calories from “ultra-processed foods,” according to a 2019 study. In a related study published two years later, the lead author wrote:

“The overall composition of the average U.S. diet has shifted towards a more processed diet. This is concerning, as eating more ultra-processed foods is associated with poor diet quality and higher risk of several chronic diseases,” Filippa Juul, an assistant professor and postdoctoral fellow at NYU School of Public Health, wrote. “The high and increasing consumption of ultra-processed foods in the 21st century may be a key driver of the obesity epidemic.”

DeVos noted that during large stakeholder conversations there is a lot of emphasis on the emergency food system and on building a local food economy.

“Neither one of those conversations are really directly addressing the issue related to people not having access to healthy food in communities where there is not a lot of money,” she said. “Neither one of those are really addressing how to change that. They’re addressing building a local food economy in places where there is a lot of economic activity, where there is a lot of extra money.”

She said too much effort is spent focusing on high-end consumers to anchor the local food system.

“Everybody is trying to go for the elusive consumer who can actually afford food. But fresh, healthy, affordable, high-quality food has been out of the reach of most of us for a very long time,” DeVos said. “I don’t see that conversation happening about a food system that’s not going after the highest-income consumer.”

DeVos said the Rescue Rhode Island Act, a $300 million legislative package introduced during the 2021 General Assembly session and meant to simultaneously address the climate crisis, racial injustice, and economic inequality, was on the right track when it came to making the right kind of investments in local food.

One of the three bills would have moved the state toward a more localized, self-sustaining food system by developing a network of community land trusts that would pay workers to produce local food in ecologically sustainable ways, according those behind the act.

Supporters of the bill noted $75 million a year for the next decade would have ensured the growth of the program, with funding specifically directed toward low- and middle-income communities. They said decisions on what to grow and how to distribute the food would be “democratically controlled” by local communities.

The bill never received a vote out of committee.

In the meantime, an increasing amount of pressure is being placed on a broken system.

The corporate takeover of the global food system, which supports such practices as concentrated animal feeding operations, is making people and the planet sick. (istock)

The corporate takeover of the global food system, which supports such practices as concentrated animal feeding operations, is making people and the planet sick. (istock)

Sick food system

The costs associated with the nation’s addiction to empty calories, sugar, processed food, and fast fare are routinely ignored — at the ongoing expense of the economy, the environment, and public health.

Largely because of processed foods — strategically placed in supermarkets and heavily marketed to children — filled with government-subsidized ingredients (e.g., high-fructose corn syrup), obesity has become a major public health problem, leaving many people undernourished and unhealthy, especially people of color and low-wealth families.

Americans consume some 30% more packaged food than fresh, and about two-thirds of adults and nearly a third of children are overweight or obese, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

America’s rising obesity rates are placing a substantial financial burden on government-funded medical programs — a cost that is ultimately shouldered by taxpayers. The percentage of Medicare beneficiaries who are obese is about 30%, and that number continues to climb.

The same communities that bear the brunt of unhealthy, hollow diets also face a high rate of food insecurity. Nationally, the rate of food insecurity for Black households is more than double that of white households, while 1 in 5 Latinos are food insecure — compared with 1 in 10 for white people and 1 in 8 Americans overall.

Climate change is taking a heavy toll on the world’s food systems, and food production itself is a major reason why, as it accounts for about a third of humankind’s annual greenhouse gas emissions. To reduce climate emissions, the world must reimagine how humans feed themselves. Producing more food at the local level is the best place to start, but the effort will also require climate-friendly crops, regenerative agriculture, streamlined supply chains, and massive reductions in food waste.

“Environmental disasters and erratic temperatures have laid waste to crops, and rising seas are salinating coastal soils. The consequences for farmers and global food supplies are obvious, as are the knock-on effects for hunger, security, and the cost of food,” according to Covering Climate Now, a media collaborative, of which ecoRI News is a member. “As usual in the climate story, it’s those who are already disadvantaged who will be hurt the worst.”

Land-use management drives food security, environmental justice, and climate change mitigation. In Rhode Island, however, despite endless conversations and taxpayer-funded studies that tout the importance of producing more food locally, already-marred spaces are largely ignored as an increasing amount of farmland is used to host ground-mounted solar arrays and prime agricultural land is covered by gigantic greenhouses to grow millions of tomatoes.

Building renewable energy on already-developed land and siting it responsibly offshore, as the Block Island Wind Farm was, would help generate the fossil fuel-free power needed to curb carbon emissions and keep farmland in production. Building massive greenhouses on already-developed areas and leaving prime agricultural land for growing would, as politicians like to say, create a win-win.

Creating a system that makes better use of the state’s finite space requires the political will; a plan to better support farmers, both veterans and newbies; mandates and incentives to build in the already-built environment; more densely built mixed-use development; public-private partnerships that place community good over shareholder profit; strengthening regional partnerships; and, of course, funding — because how humans use the natural world impacts biodiversity, which supports healthy food systems.

Rhode Island is already doing some of this work. For example, Rhode Island Commerce ($610,000) and RIHousing ($755,000) helped fund SCLT’s new $6 million Broad Street facility. The Conservation Law Foundation supplied a $750,000 low-interest loan.

This new-look, land-use/food-production system needs committed support and increased investment, redirecting money, tax relief, and applause from such projects as a 600-foot-high luxury residential tower in Providence, a woodland-built office park that promised to “integrate wildlife paths for habitat circulation,” and a video game company that quickly went belly up.

DeVos said this rebuilt system would also require infrastructure on the microeconomic level and the streamlining of the state tax code for small-scale food businesses.

Diversity of human knowledge and cultures in this revamped system of land use would also help Rhode Island fortify its food system and protect its environment. One way to accomplish that is to incorporate the agricultural practices of Indigenous people that work harmoniously with the natural world.

The current system — monolithic agriculture run for profit by a handful of multinational corporations — isn’t healthy for people or the planet. (Four corporations currently control more than 50% of the world’s seeds and dominate the global food supply.)

“Acknowledging the importance of biodiversity is critical for our food security, for sustainable development and for the supply of vital ecosystem services,” according to Slow Food International, a global, grassroots organization founded in 1989 to prevent the disappearance of local food cultures and traditions.

Slow Food advocates for public money for public goods: only agroecological farming systems contributing to the socio-cultural, economic, and environmental sustainability of their local areas should receive financial support from governments.

The organization has noted “ever-increasing economic growth and inequality, industrialized food systems, excessive consumption levels, corporate capture, and a naive belief that technology will be able fix any and all problems” are contributing to biodiversity loss.

“Biodiversity is the diversity of all life, from individual genes to species up to the most complex levels, ecosystems. Without a variety of living forms, life itself would disappear, because it would lose the capacity to adapt to changes,” according to the first paragraph in a 2020 Slow Food position page on biodiversity.

The 75-page paper notes: biodiversity allows agricultural systems to overcome environmental shocks and changing climates; it provides ecosystem services that are essential to life, such as pollination; and it allows the production of food with a minimal impact on non-renewable resources, such as water and soil, and with less need for external inputs that are costly and harmful to the environment, like fertilizers and pesticides for plants and antibiotics for livestock.

Broad action is required at the local and global levels as food production systems worldwide are becoming less diverse. The narrow focus of the corporate food industry “on a handful of vegetable varieties and animal breeds leaves our global community more vulnerable to climate breakdown, future pandemics, widespread malnutrition and hunger,” according to Slow Food.

The Slow Food USA chapter says the “economic push for speed, growth and profit has created mega food systems that are unsustainable.”

“Instead of building relationships around food, we make transactions. Instead of making food choices based on flavor and origin, we prioritize convenience. Instead of treating the Earth like the source of all life, we pillage resources from our planet,” according Slow Food USA. “Our food policies maintain a power imbalance that disproportionately affects Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC), low-income communities and women. Theft of land and water, worker exploitation, lack of access to nutritious foods, food apartheid, and diet-related health problems are rooted in racism, classism, gender discrimination, and other oppressive practices.”

The solution lies with building robust local food systems that put feeding all people ahead of making millions for a few already-wealthy individuals. Food, like housing and health care, needs to be treated as a human right and not a commodity managed by CEOs and CFOs.