The Young Farmer Network, an informal group of farmers in Southeastern New England, works to bridge knowledge gaps and battle the isolation and burn-out of farm work with workshops, social gatherings and farm tours. On March 16, YFN hosted “Stories of the Land” an oral history presentation and workshop at the Southside Cultural Center to help educate farmers and community members about the history of their land.

The central theme of the event was that it is important for people to know and tell the history of the land on which we live and work. The event featured three people of color, accomplished historians and activists, including Professor Christy Clark-Pujara of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Lorèn Spears, Narragansett educator from the Tomaquag Museum and Marta Martinez, executive director of RI Latino Arts. Local historian Tim Cranston from the South County Independent was also present.

The history taught was about Rhode Island’s deeply entangled relationship to slavery: more than 80% of slave ships that departed from North America left from a port in Rhode Island and, in 1750, 10% of the state’s population was enslaved —twice the Northern average.

“The business of slavery is distinct from the institution of slavery, but it allowed New England to become an economic powerhouse without ever producing a single staple crop,” said Professor Clark-Pujara. Her research helped put an important emphasis on the business of slavery, which she defines as “all economic activity that was directly related to the maintenance of slaveholding in the Americas.”

For instance, she described the manufacture of Negro, or slave, cloth—coarse cotton material milled primarily in Rhode Island. “You get a textile manufacturing industry in Rhode Island in the antebellum period that is doubly dependent on slavery,” she said. “They are importing slave-grown cotton and then selling it back” to those who picked it to be made into their own clothing.

It is also important to familiarize ourselves with the voices and perspectives of those who are enslaved, victimized or otherwise oppressed. Clark-Pujara shared that when she began her dissertation on slavery in the Northern United States, many people told her she could not center a book on the black experience in the Colonial era, because the sources were not there and she would not be able to tell a story.

As it turned out, she did find those sources. And, she warns us to be mindful about historical accounts, even ones that acknowledge violence and atrocities, because they oftentimes deny “victims” a voice that articulates their lived experience. In fact, “Enslaved people asserted their humanity in an inhumane system. They were full people and they did their very best to live full lives,” she said.

“I always try to remind people that enslaved people were not just acted upon, that they reserved a little something for themselves.”

What I was most humbled to take away from “Stories of the Land” was the realization that it is not enough to familiarize myself with the historical facts of the slave trade. It is even more important to acknowledge that, while my European ancestors did not participate in either the institution or the business of slavery, they benefited from the strong U.S. economy that resulted from both. That includes being able to work, receive a meaningful education and buy property in such a prosperous, stable economy (while slaves, former slaves and their descendants were excluded from these benefits). These benefits continue to accrue to my family and to me.

Thinking about this has meant a new path in the direction of food justice, one that accounts for the environmental, economic and societal effects of manifest destiny, slavery, the prison industrial complex and redlining. It is a path that aspires to recognize all of the injustices that arise when people of color, indigenous communities, immigrants and refugees are prohibited from living full lives.

This is not a new path for many members of our community. Leaders of color, Black, Brown, Indigenous and Latinx farmers, white allies, activists and historians like those at the workshop, have been on the path of justice their entire lives. They are the experts who have so much to share. In a climate characterized by uncertainty and turmoil, one of the best ways I can take a step in the right direction is to take a step back, listen and begin to understand our shared history.

– Maggie Nowak, SCLT Farm, Food & Youth Coordinator

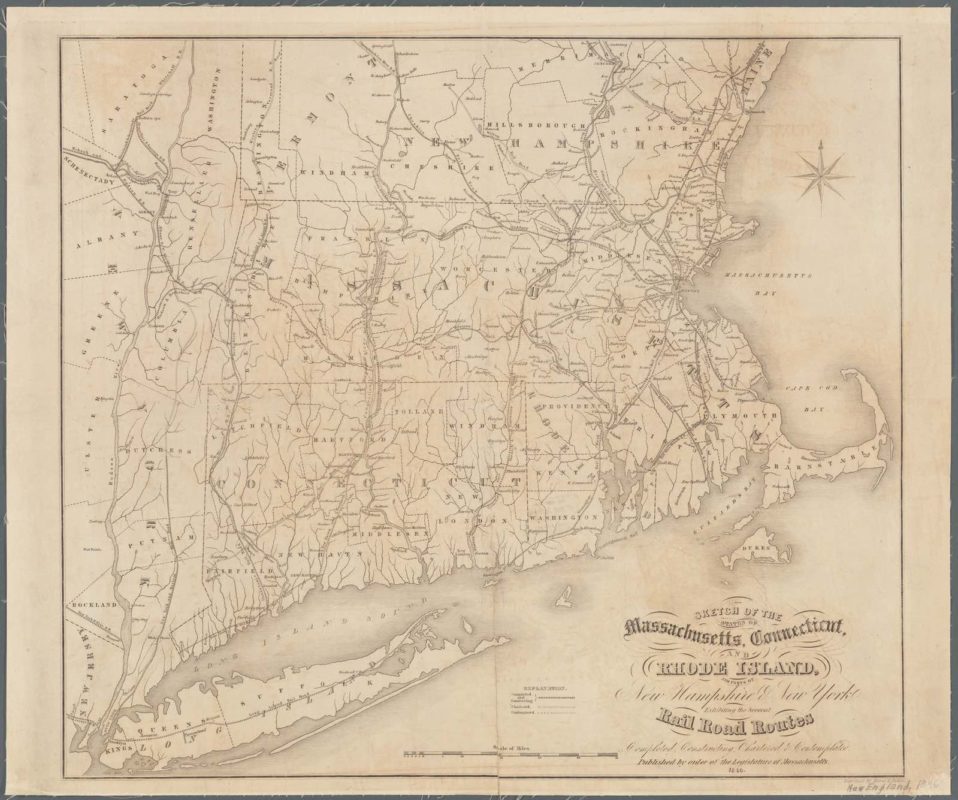

Historical map courtesy of the New York Public Library’s Lionel Pincus & Princess Firyal Map Division

Want to learn more?

- Check these books: Christy Clark-Pujara’s Dark Work: The Business of Slavery in Rhode Island, and Leah Penniman’s Farming While Black

- Visit the Tomaquag Museum in Exeter, RI

- Join Marta Martinez or her colleagues on an Este Es Mi Barrio (“This is My Neighborhood”) walking tour

- Check out the Young Farmer Network for upcoming workshops and farm tours.